Notes from a Greek island: AI, Creativity, and The Death of Socrates

I love coming to Greece, I feel like it's my ‘spiritual home’. As the birthplace of what we might call Western Philosophy, its history and culture always make me reflect on the world and my place in it. I’m in Mykonos, where Heracles is said to have lured and defeated the giants during that epic mythic battle known as the gigantomachy - the huge rocks around the island representing their petrified bodies. This is a place where big ideas, thoughts of gods and giants, are as natural as a stroll on the beach.

Those close to me know that ‘vacationing’ is not a strength of mine, but these breaks allow me to spend quality time with my family, and also give me an opportunity to do some deep thinking. Right now I’m on the ‘Zeus’ - the same superyacht that Elon Musk famously vacationed on (you may remember the shirtless photos). I count myself incredibly fortunate to be able to do this. Like Musk and many others who are lucky enough to gain some economic freedom, I choose to work because I believe that what makes us truly happy is not just living for ourselves, but for others. This is still the purpose of Satalia, and is in the concluding remarks to many of my keynotes on the promise of AI and its impact on humanity.

The main focus of my work now is how to create a world where AI and humanity can thrive together, and sometimes doing your best work means taking yourself somewhere where you can think. This literal ‘change of scenery’, and the inspiration that the Greek landscape and culture provide, have my thoughts turning back to something I’ve been preoccupied with over the past few years and more so recently - the relationship between AI and creativity.

The Death of Socrates

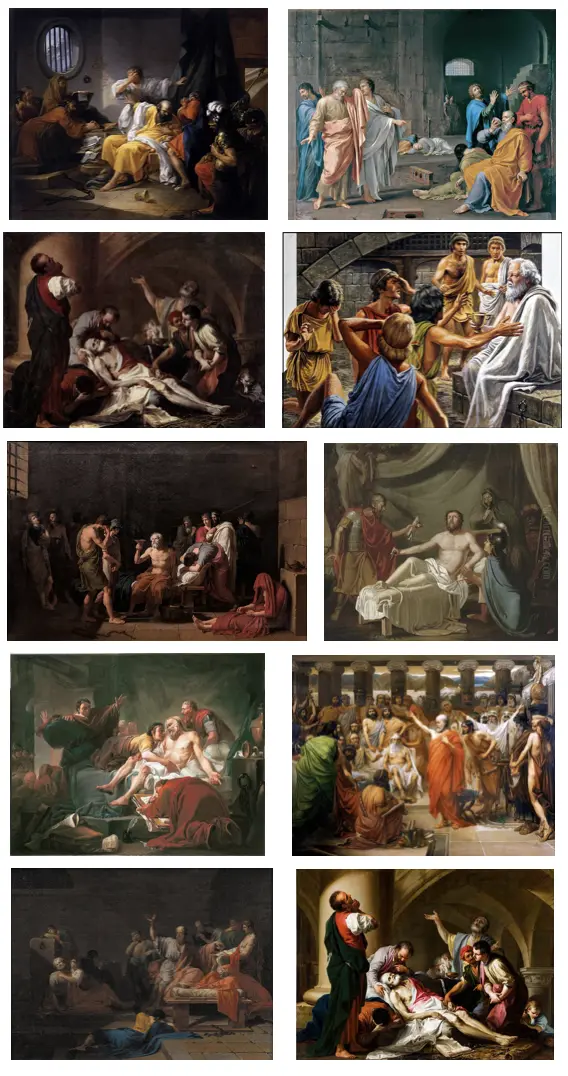

Greece was, of course, home to the great early philosophers of western civilisation - including Socrates - thinker, orator, mentor, and ultimately martyr to his beliefs. He is also the subject of one of my favourite pieces of creativity, the great neoclassical painting ‘The Death of Socrates’ by Jacque-Louis David. This painting fascinates me not just because of its aesthetic and symbolic quality, but because of the way it has been received by the world. It is widely considered the best rendition of this particular event - Socrates drinking the hemlock that would result in a most painful death. At the bottom of the page you can see some of the other renditions that have been attempted through the ages.

This has me thinking - what does it mean to produce a great depiction of a historical event? Or a great depiction of anything for that matter? Jacque-Louis David was working in the eighteenth century, more than two millennia after Socrates’s death, and his sources will, therefore, have been second-hand - writings and stories passed down through the generations and interpreted in the context of the culture of the day. A little bit like the data LLMs have access to and are trained on.

Why then is this rendition revered as one of the greatest artistic representations of this scene, compared to the ones at the bottom of the page? This is a matter of opinion - the opinion of those with expertise and power: critics and tastemakers who have deemed this version superior, and who have shared this view with the world through the media. In previous centuries, these respected authorities were the influencers of good taste. But in today’s more fragmented media landscape, who determines what is ‘good art’? Furthermore, are machines ‘allowed’ to produce good art in our culture? Can a machine understand, or even have, ‘taste’? What even is ‘taste’?

AIs are, of course, capable of producing thousands, millions of different renditions of an idea, a story, an image, based on the prompts we give them. How then might we determine whether any of these represent ‘genius’ in the same way as we use the term in relation to human-generated art? How might we decide whether this is truly creative brilliance? Does it even matter?

The Monet Problem

If LLMs can now produce something that looks entirely ‘plausible’ in relation to normative expectations of a painting of a classical subject, what about their ability to make the kinds of creative leaps humans have made?

The Impressionists (along with other art movements like cubism, surrealism) managed to produce artwork that appears to us as truly innovative, whether through colour, form, or concept. If we humans can achieve this, can an AI?

Gen AI is perfectly capable of producing images in the style of David, Monet, or any number of artists whose work it has been trained to understand. The problem we are then faced with is this: which one of the many - perhaps infinite - possible renditions is the ‘best one’? I call this The Monet Problem.

More specifically, there are two Monet Problems; two problems that challenge the notion of AIs’ creative capacity. The first is characterised by asking ‘what is the very best rendition, out of the infinite renditions, of X “in the style of Monet” (where X can be anything from Terry the Tiger to The Death of Socrates)?'. The second problem asks ‘can AI discover a new genre that has never existed, in a similar way in which Monet is considered the founder and driving force behind impressionism, and Picasso that of cubism?’.

When faced with situations where there are too many options, it is much harder for humans to choose - something which marketers know only too well, and exactly what ‘branding’ is designed to solve for. I believe that this choice-making, too, is a task we are likely to begin to offload to ‘critic’ agents, who will be trained to select the ‘best’ version for us.

The AI tools we have today are already able to come up with creative advertising campaigns that can win the top awards in the industry. This suggests that their outputs can be as creatively valuable as those produced by humans, but these are outputs in response to a brief. What would AI be able to produce if, like us, it had its own creative urges, curiosity, and the time to think, and play?

These thoughts bring me full circle, back to questioning what our understanding of AI is, what it could be, and whether it may, at some point, be capable of consciousness and intrinsic intent. These are the difficult questions I and my team (several of whom are based here in Greece) are trying to answer. What I do know is that we are entering a new era of AI-enabled creativity, and possibly even AI-led creativity. What a privilege to be able to sit and think about this as I look out at the sun going down over the beautiful Aegean Sea.